Across the world, centre-left governments and the traditional parties of the working class are in crisis. Reformism has hit up against the rocks of reality, unable to offer anything to workers and youth in this age of austerity. Daniel Morley examines the crisis of social democracy and points the way forward for leaders, such as Corbyn, in the fight to defend the gains of the past.

When one takes the broadest possible perspective on the history of capitalism, distinct political and economic epochs are detectable, such as the upswing of the late 19th Century, the profound crisis and imperialist disintegration of the two world wars and depression, and the renewed upswing after WWII. One tendency that stands out is that the upswings tend to be accompanied by a strengthening of reformism or social-democracy, and the downswings by its weakening and by polarisation. This process is neither linear nor mechanical, and any generalisation must be extremely conditional and open to exceptions. Nevertheless, such a pattern does seem real.

Today’s epoch has many unique features. But it is crystal clear that we live in an epoch of profound capitalist decline - one that has greatly accelerated since 2008, but that in truth has been with us since the mid-to-late 1970s. It is in this context that we should understand the unprecedented degeneration, decline and even destruction of traditional social democracy in many countries, especially European ones.

The Economist (2nd April 2016) reports that across Europe social democrats are at their lowest level of electoral support for 70 years, falling by on average ⅓ over the past few years! “In the five European Union (EU) states that held national elections last year, social democrats lost power in Denmark, fell to their worst-ever results in Finland, Poland and Spain and came to within a hair’s-breadth of such a nadir in Britain.” Even ‘naturally’ social-democratic Sweden has ‘matured’ into more of a normal capitalist country with austerity and privatisation.

Across the advanced capitalist world, the film of capitalist development seems to have been running in reverse for decades now. Just about the only thing growing in these economies has been inequality, and everybody knows it. It is widely known that the wages of the US working class have stagnated or even declined for many years, even decades. The net worth of working class Americans declined by 53% between 1998 and 2013 (The Guardian, 19th May 2016). The Financial Times reports that “Millions of Americans are anchored to blighted neighbourhoods by negative equity, or other ties that bind. Their life expectancy is falling. Their participation in the labour market is dropping. The numbers signing up to disability benefits is rising. Opioid prescription drugs are rife.” (FT, 21st March 2016).

It is hardly surprising then that The Economist (19th March 2016) recently found American workers felt that “Obama is for the people who don’t work” (i.e. the super rich). “Strikingly, praise for the president was mostly dwarfed by anger at the state of the country...Asked to sum up Mr Obama, the men replied variously that he was a good man, a disappointment, a ‘great speech-giver”...and a man who had failed to reign in the super-rich and their influence over politics.” The article adds that “Jeff McCurdy, a warehouse worker, described colleagues struggling to raise families on salaries of $14 an hour. “Their kids aren’t even getting the healthy food they need...and they wonder why people are pissed off.”

The inescapable conclusion these facts of modern life drive towards was, surprisingly, hinted at by this arch-capitalist newspaper:

“The men in the union hall want a new approach to capitalism, in which foreign trade partners must pay living wages and heed global environmental norms...they feel - passionately - that the economy is stacked against them, and want larger changes to capitalism than mainstream politicians can deliver. What then?”

Readers would do well to read Kevin Williamson’s article for the National Review magazine to get an honest account of how these ‘mainstream politicians’ view such angry men and women in union halls (or ‘working class whites’, as the article calls them). In this article, Williamson baldly states that,

“The truth about these dysfunctional, downscale communities is that they deserve to die. Economically, they are negative assets. Morally, they are indefensible. Forget all your cheap theatrical Bruce Springsteen crap. Forget your sanctimony about struggling Rust Belt factory towns and your conspiracy theories about the wily Orientals stealing our jobs. Forget your goddamned gypsum, and, if he has a problem with that, forget Ed Burke, too. The white American underclass is in thrall to a vicious, selfish culture whose main products are misery and used heroin needles. Donald Trump’s speeches make them feel good. So does OxyContin. What they need isn’t analgesics, literal or political. They need real opportunity, which means that they need real change, which means that they need U-Haul. If you want to live, get out of Garbutt.”

The truth is that such men and women have always viewed the working class this way; what stands out now is that the mass of the working class all over the world are conscious of it. In particular, they are conscious that ‘their’ social democratic leaders now enthusiastically share this class hatred of the ruling class. If anything, the likes of Angela Eagle, Francois Hollande and Sigmar Gabriel appear even more contemptuous of their working class voters than do the conservatives.

The situation is no different in Britain and Europe. All over Britain we find dilapidated high streets in which the only new shops are 99p stores. Since 2008, only one in every 40 new jobs created has been for a full-time employee. Work has been hollowed out and replaced with zero-hour jobs. Britain has experienced more deindustrialisation than any other major nation, though rust belts and the wreckage of decaying capitalism are now normal features of all advanced capitalist societies. The ongoing Sports Direct enquiry has revealed that this major company doesn’t even pay the legally required minimum wage, refuses to allow toilet breaks, and witnessed several births in its warehouses because it refused maternity and sick leave. Sports Direct embodies the generalised attack on the position of the working class across the country, and what is really needed is a trial of the whole capitalist class in Britain, which is no different to Sports Direct owner Mike Ashley. Similarly, BHS’s collapse while its bosses lined their pockets is a fitting epitaph for the British capitalist class as a whole.

Crisis of bourgeois democracy

In truth, what we are witnessing is the beginnings of a profound crisis of bourgeois democracy as a whole. The so-called anti-establishment mood corrodes the mainstream right wing as well as the social-democrats. The phenomenon is so widespread it stretches even to ex-colonial countries such as India and the Philippines, which has just elected its own ‘Filipino Trump’. Where in the world can one find a confident and popular mainstream bourgeois or social-democratic party? Until recently, one might have said Germany, but the CDU is now rapidly losing credibility to the reactionary AfD on the right, and the SPD has been in crisis for more than a decade now.

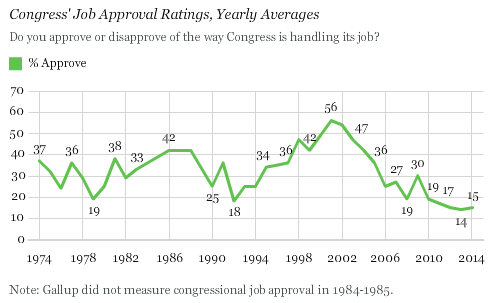

Opinion polls across the advanced capitalist world consistently show profound (and unprecedented) mistrust and even outright contempt for politicians and the media. In the US, Congress has an approval rating of 15-18%, an all time low. The level of disdain is the same amongst Democrat and Republican voters. This graph shows the dramatic decline in support in recent years:

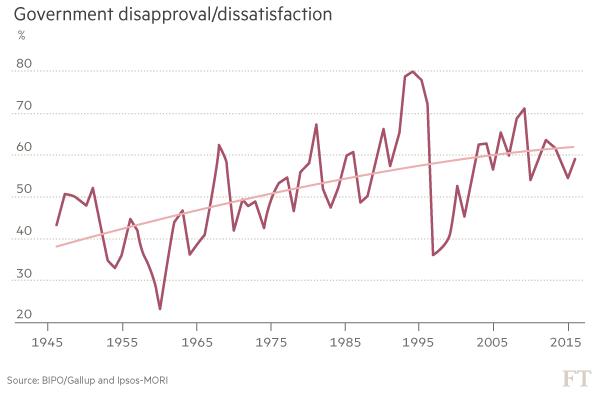

The percentage of Europeans disapproving of the whole democratic system in their country has climbed significantly, now reaching 45%.

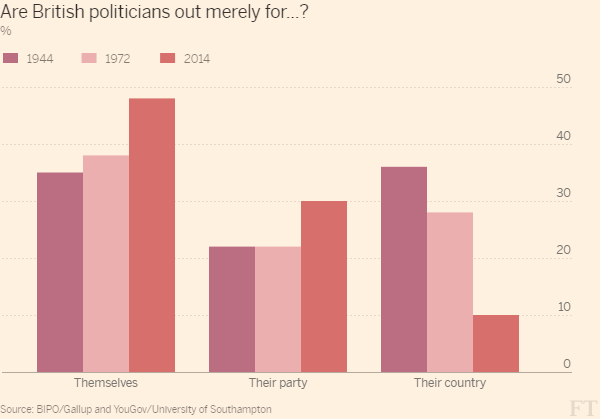

These visceral ‘anti-establishment’ feelings are extremely widespread in Britain and represent a complete loss of faith in bourgeois democracy. The Financial Times quotes from a powerful study by Will Jennings, a professor of politics at Southampton University:

He has studied British attitudes towards the political establishment since the 1940s. The conclusion: trust has eroded steadily over decades, but is now running alarmingly low.

The UK’s Mass Observation archive, which collects diaries and other private correspondence, shows that people today write about doctors, the clergy and lawyers in more or less the same way as they did back in 1945. That is not the case with politicians, as a recent paper co-authored by Professor Jennings points out: “Citizens now described their ‘hatred’ for politicians who made them ‘angry’, ‘incensed’, ‘outraged’, ‘disgusted’ and ‘sickened’.”

Among the words used for politicians, the paper adds, are arrogant, boorish, corrupt, creepy, devious, loathsome, lying, parasitical, pompous, shameful, sleazy, slippery, spineless, traitorous, weak and wet. As Prof Jennings says, “whatever measure you use political mistrust is rising — you see a generalised malaise”. (Financial Times, 15.6.16)

This is spelled out vividly in the following graphs:

Widespread is the sense that ‘the system is rigged’; that the entire ‘system’ must be fundamentally changed because its structure is wrong or broken beyond repair. The conceit of our much vaunted democracy is that the people are sovereign, and that is the assumption of our education systems and most public debates. Actually, the democratic system is subordinate to the economic system of capitalism. There is never any real ‘national sovereignty’ under capitalism, it is always really the rich business owners that dominate. In today’s epoch of the crushing domination of the world market, the illusion of national sovereignty has been greatly weakened, but of course it is the ongoing crisis of capitalism which has dealt the harshest blow to this illusion.

The unforeseen financial and economic crisis dramatically altered politics across the world against the will of all participants, conservative and social-democratic. All politicians must now worship at the altar of balanced budgets and endless austerity. Well before the financial crisis the social democrats had abandoned the pretence of standing for anything significantly different than the conservatives. But the financial crisis has cruelly exposed their sheer emptiness, their inability to fight for anything. This was most graphically revealed in Greece of course, first with PASOK and then even more dramatically with Syriza. But the inability for ‘democracy’ to control the market has been revealed also with Hollande in France and the PSUV in Venezuela. Voters everywhere can see that if they elect a left-reformist government, it will immediately face a flight of capital and an economic crisis, and its capitulation to ‘the markets’ will likely be as swift as it is ignominious.

The crisis has revealed precisely that the system is rigged, and that bourgeois democracy is a sham. This realisation must fall most heavily onto the social democracy, since it is these parties that bear the burden of ‘proving’ that through ‘democracy’ we can tame capitalism. It is social democracy that is most heavily invested in the illusion of the sovereignty of the people. These words of Trotsky referring to the dilemma of social democracy during the Great Depression are extremely relevant today:

“The crisis did not strengthen the party of ‘socialism’, on the contrary, it weakened it, just as it depressed the trade turn-over, the resources of banks...Today, one is obliged to look, not in bourgeois papers, but in social democratic press for the most optimistic evaluations of the conjuncture...If the atrophy of capitalism produces the atrophy of the social democracy, then the approaching death of capitalism cannot but denote the early death of the social democracy. The party that leans upon the workers but serves the bourgeoisie, in the period of the greatest sharpening of the class struggle cannot but sense the smells wafted from the waiting grave.”

A crisis decades in the making

The truth is that social democracy is utterly dependent on the health of capitalism. It rides its waves, carrying out reforms when the economic conditions merit it, but finds itself bewildered and dumbstruck by capitalism’s periodic crises. Incapable of really challenging the ruling class, trying instead to persuade it, it is always unprepared for the ruling class’ attacks. Reformism necessarily must fail to anticipate the inevitable consequences of its attempts to regulate the market, such as inflation and capital flight, because it is based precisely on the illusion that clever politics can eliminate the injustice and anarchy of the system. Therefore its plans founder on these rocks of reality.

It is failures of this kind in the 1970s that dealt the initial blow from which social democracy has never truly recovered. The Wilson-Callaghan government of 1974-9 was elected on a radical platform, pledged to nationalisation on a big scale. But the postwar boom had by now thoroughly exhausted itself. The shocks of the oil and Bretton Woods crises shifted the thinking of the capitalists to monetarism and ‘neoliberalism’ away from Keynesianism. This wrong-footed the Labour leadership, who neither anticipated nor understood the long-term significance of this. Their government was wracked by rampant inflation, capital flight, the collapse of sterling and a humiliating bailout by the IMF.

Just like Syriza, the Labour government did a 180 turn and swallowed the IMF’s austerity agenda, abandoning the entire left programme it was elected on. Another example at a similar time is that of Francois Mitterand’s ‘austerity turn’ two years after being elected on a left wing programme in 1981. It is the same also with Ramsay MacDonald’s shameful treachery in the crisis of the 1930s, when he abandoned his programme and party to form a government of austerity with the Tories and Liberals.

It is important to emphasise how unprepared the reformist leaders were for this, since this lack of foresight is characteristic of reformism, which assumes vainly that capitalism can be tamed or made rational. It is also important to emphasise the ruling class’ decisive shift away from the Keynesian ideas that were complementary to social-democracy. These are important to emphasise because they show the decisive importance of the anarchic, unplanned movements of the market in dramatically changing and limiting the political process in capitalist society. It is precisely this feature which reformism cannot grasp or accept.

In truth social democracy, in Britain at least, has been AWOL ever since then. It has never recovered its nerve, because its nerve was based on the assumption, now thoroughly exploded, that the capitalists and their system were permanently compatible with high taxation, deficit financing and a big welfare state. We are all used to the strangely empty, vague and platitudinous character of the speeches and pledges of reformist leaders in modern times. In a recent notorious interview, Angela Eagle found it impossible to say what the political basis to her challenge of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership was. She simply had nothing to say, no political content at all. This is because she and her ilk have had their options destroyed by the capitalist system’s crisis. In fact we know what her political content is; her voting record demonstrates she is a supporter of austerity and war. But she cannot say this openly, so she says nothing.

The social democrats could have drawn the lessons from this experience: that it is not possible to reform your way to socialism gradually. They could have, faced with the strike of capital, mobilised the working class to fight this, called for the workers to support the expropriation of capitalists undermining the economy, etc. But to do so would mean to challenge capitalism with revolution. Instead they were paralysed by the shock, and simply caved in to the demands of austerity. This unedifying picture caused Labour’s ejection from office in 1979, and the rest is history.

For these reasons the social democrats have a reputation in most places for being rather pathetic, vacillating, unprincipled and afraid of or disgusted by their own working class base, alongside their much discussed reputation for economic mismanagement. Why can they not recover their former popularity?

Rotten ripe

In 1938’s Transitional Programme, Trotsky pointed out that the conditions for the overthrow of capitalism had become somewhat rotten ripe. If capitalist decline is not translated into socialist revolution, bourgeois society rots. In place of socialism we got fascism.

The post-modernists like to talk about the end of ‘grand historical narratives’, especially that of capitalism’s socialist overthrow. They declared an end to progress and rationality, and retreated into subjective experience and interpretation. This is a cynical and directionless philosophy, utterly useless for anything other than justifying the preservation of capitalism and, of course, intellectual sophistry. But all influential philosophies are influential for a reason; they must reflect something that is true.

What postmodernism does reflect (though uncritically), is precisely this rotten-ripeness of the socialist revolution. The ‘end of grand narratives’ is really the failure of proletarian leadership in the epoch of social revolution.

When one looks at the deindustrialised wastelands of Europe and North America, at the mass alienation from politics, at the cynicism and emptiness of mainstream politics, it is clear that capitalism has reached a sort of dead end and begun to decline. The system is decaying. In truth, it temporarily went beyond its limits in building big welfare states, and must now devour these working class encroachments.

Wrong-footed by the crisis of the 1970s, unprepared for the attacks of the bourgeoisie, the reformists, committed to managing capitalism, had no choice but to accept the supremacy of the market. The Thatcherites did a very thorough job of attacking ‘socialism’; the defeat was humiliating for the Left. In Britain, once the miners were defeated, the guts were ripped out of a defenceless labour movement. The working class largely withdrew from political activity, and the careerists at the top of social-democracy had a free hand to carry out their wholesale capitulation to ‘neoliberalism’.

Today, it is the combination of that hollowing out of these parties, and the current severe crisis of capitalism, that produces the empty soundbyte politics of these parties. This surreal emptiness reached its height under Ed Miliband, who on the one hand felt the need to position Labour to the left of the Tories and try to make political capital by criticising austerity, but on the other hand entirely accepted the need for austerity and for Labour to be seen as ‘economically responsible’. He was rightly seen as weak, confused, unprincipled and a world away from the burning anger of the working class.

Prior to last summer’s Labour leadership election, the entire party seemed to be sleepwalking into death. There was a constant vain searching for a magical recipe for success, but there were never any actual ingredients making up this recipe. This or that MP would come forward and talk incredibly vaguely about the need for some mysterious new ‘strategy to get our message across’. But they had no message, and never could have, because they accepted that it is their job to manage a capitalist system in deep crisis. This debate was very noisy and yet strangely empty - but then again an empty vessel does make the most noise.

The Left must throw caution to the wind

The bourgeoisie’s perspective for social democracy in this fractured political landscape is for it to collapse into a sort of niche party in the patchwork of political interests. For them, being working class is just a superficial identity, so social democratic parties may retain their strength in regions that happen to retain an explicitly working class identity, like Newcastle or Germany’s Ruhrgebiet. Even then, such loyalty can and will be whittled away if the party fails the express the real interests of working class people, as Labour’s position in Scotland shows. This is perhaps the future for social-democracy if it fails to break out of its inertia and fight for the interests (rather than the mere cultural image) of the working class.

There is burning anger in the working class across Europe and North America, a sense of betrayal and extreme alienation from politics. It is more than just anger at economic injustice, it is also frustration from the lack of any sense of control over politics. Many have noted how support for Trump often increases when he makes what the media perceive as a ‘gaffe’. Many probably don’t agree with, or think particularly coherent, his rude, racist and sexist remarks. But this misses the point, people don’t support him for the coherency of these remarks; they support his tearing up of the so-called rulebook. They are delighted to see someone who seems to echo their sentiment that ‘your politics, your rules, your values mean nothing to us!’ They like that he does not care about the contrived manners of mainstream politics because they correctly discern that these manners are a phoney gloss on a lie.

Part of Trump’s popularity is that he has thrown caution to the wind. But the Left still seems to be apologising for itself to the ruling class, still seems afraid of its own shadow. Prior to the present crisis and leadership election in the Labour Party, even Corbyn and McDonnell seemed excessively cautious, afraid of unleashing the pent up anger of their supporters. McDonnell was keen to spell out his economic ‘responsibility’ and ‘iron budget discipline’. In most countries the social-democracy still seems scarred from its defeats, still seems to believe the propaganda of the right wing. It is afraid to throw off its shackles because it knows it must manage a decrepit capitalist system and cannot raise expectations too high. But that is fatal for it, it can only revive by reflecting the masses’ militant anger and passion. In this way the crisis of social democracy reflects the crisis of the capitalist system.

In truth society has moved to the left since 2008. There is a radicalisation and a desire to express the anger built up at the injustices of the past two or three decades, to come to a reckoning with ‘the establishment’. Hence the unprecedented vote for Brexit, which has dramatically accelerated all these processes. The anger is beginning to find an expression: in many countries outside of the traditional social democracy (e.g. in Spain and Greece); in Britain through an unprecedented change in the Labour Party.

The enormous gap between the anger and neglected interests of the working class, and the political situation, has finally begun to narrow. For years we’ve been told by post-modernists that mass political parties are a thing of the past; that everyone now is interested only in single issues and is essentially just a middle class individual. But events have changed everything. Labour is now the biggest party in Europe, with close to 600,000 members. All the perspectives and theories about society and politics that were dominant are being falsified. A gigantic class struggle is opening up in the Labour Party. The gulf between the working class and the party membership on one side, and the MPs on another, is actually wider than ever. But now this class consciousness and anger is not passive, it has an outlet and is growing in confidence and boldness with each clash in this struggle. The genie is out of the bottle and cannot be put back.

We are witnessing in Labour the painful rebirth of the socialist movement and class based politics. Social democracy and class collaboration are in their death throes. Corbyn and his movement are not the end of this process, but only the confused beginning. He himself remains reformist. But there can be no doubt about it - we are living through the death of social democracy as we have known it.

The political radicalisation we are witnessing is a messy process. It is almost like the movement is starting again. We will see wave after wave of radicalisation from country to country. In some countries the existing social democracy will be transformed and shaken up, as we can see with Labour in Britain. In others new formations will arise, as with Podemos in Spain.

In both cases these phenomena will be very unstable and most likely short lived, because until they break with capitalism they will, in an epoch of crisis, be overwhelmed by the crisis of capitalism and be forced to abandon their programme, as seen with Syriza. There is and will be an almighty churn of left wing, and right wing, parties all over the world. Through the din and confusion of this process a clear note rings out: “the people demand the fall of the regime!”

The regime, that is capitalism, has exhausted itself. There is no room for reformism to carry out reforms. Fundamentally that is why social democracy is in crisis. It can only shake off the stench of betrayal by ‘throwing caution to the wind’. It must abandon the attempt to manage capitalism, a doomed mission, and boldly embrace the fight for a socialist alternative to capitalism. Fighting talk and clear alternatives are what the working class needs and wants.